Looking for new ways to engage all your students and get them to think more deeply and critically about a text? Consider trying a Socratic seminar. This formal, guided discussion method encourages students to take the lead and share their thoughts in meaningful ways. Learn how it works, plus fill out the form on this page to grab a free printable list of Socratic seminar questions to try with your class.

Many people are familiar with the Socratic method, used by the famous Greek philosopher and teacher Socrates. Rather than lecturing, Socrates would ask his students thought-provoking questions and encourage discussion on the topic. As students answered, they began to draw their own conclusions by thinking critically. Rather than passively receiving information, students actively worked their way to knowledge through discussion and critical thinking. This method is still used today in many fields, such as the study of law or philosophy.

In the early 21st century, educators like Laura Billings and Terry Roberts popularized the Socratic seminar teaching method, a collaborative guided discussion on a specific text. It uses many of the same strategies as the Socratic method, but focuses on encouraging students to think collaboratively and critically, citing examples from the text to support the points they make in a discussion. Students prepare in advance, reading a text with specific questions in mind. Teachers usually start the discussion by asking open-ended questions, then guide it only as needed along the way.

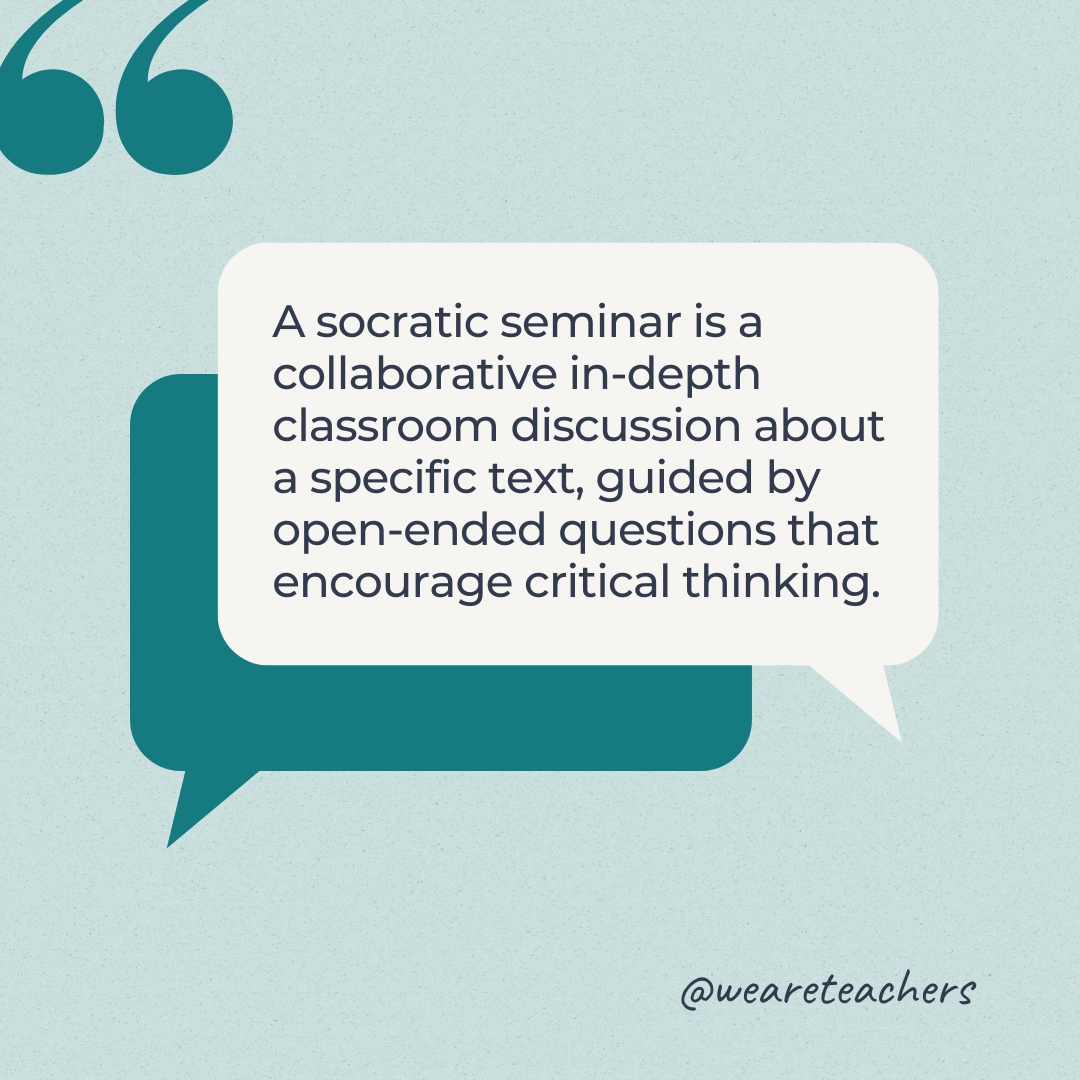

Billings and Roberts noted many benefits to using this discussion method in the classroom. It gives students a chance to develop:

When students discuss a text using Socratic seminar questions, they must think deeply and critically about the subject. Rather than just sharing their opinion, they must cite passages from the text that support their thinking. This encourages them to apply important critical thinking skills by analyzing and evaluating the information carefully.

As students work to form educated conclusions in answer to the Socratic seminar questions, they must listen and build off each other’s responses. They work together to revise and refine their conclusions, taking everyone’s contributions into consideration. It’s a powerful way to find creative answers and common ground.

Students participating in a seminar must both speak and actively listen. They learn to present their ideas clearly, using passages from the text to support their views. Active listening plays a huge role, as students take notes while others talk and gain new perspectives. Students must also ensure everyone feels safe and comfortable contributing to the discussion, welcoming diverse perspectives about the topic.

Participating in class discussion is hard for some students, but this seminar style can help build their confidence. Because students prepare in advance, they can feel more comfortable when it’s their turn to contribute. Over time, they develop confidence in their communication and discussion skills, which benefits them both in and out of the classroom.

When students prepare a text for discussion in a seminar, they spend more time thinking deeply about it. This helps them feel more personally connected. Class discussions tend to reflect the ideas and values students feel are most important, making the learning (and the text) more relevant to everyone.

You’ll most often find this learning method used in English language arts and social studies classes like sociology, history, or ethics. But it can be applied to any subject where students read and evaluate a piece of writing, including magazine or online articles.

ADVERTISEMENTSocratic seminars work for any age where students are capable of reading a text on their own and making notes in response to questions. Even elementary-age students can participate, although they’ll likely need more guidance as they learn what’s expected of them before and during the discussion.

Since students are largely responsible for their own learning in these seminars, they’re actively involved in both preparation and discussion. To prepare, students read the text and take notes. Teachers usually provide a list of questions in advance, so students can highlight or otherwise mark the parts of the text they feel are relevant. This prepares them to participate effectively in class.

During the conversation, students take turns responding to the questions, citing textual evidence to support their answers. They also listen actively as others talk, making notes so they can ask questions or respond to others when it’s their turn to speak again.

In larger classrooms, teachers sometimes use what’s known as a “fishbowl discussion.” A small group of students sits in a circle and participates in the initial discussion, while the others sit around the outside and take notes. After the smaller group completes their discussion, the outer circle adds their own thoughts based on what they observed throughout.

This is one of the most important steps, since the right type of text ensures a successful seminar. You can use a wide array of texts, including poems, stories, historical documents, newspaper or journal articles, speeches, and more. Good Socratic seminar texts are:

Next, consider what you want students to take away from their discussion, and develop questions that help students consider those concepts. Socratic seminar questions must be open-ended and often have no right or wrong answer. Our printable list (below) can help you develop the right questions for your seminar.

Generate a list of 8 to 10 questions you might use during discussion, bearing in mind that students may only get to a few of them depending on the depth of their discussion. Narrow that list to four or five key questions to share with students in advance.

If students are new to Socratic seminar, explain how it will work in advance. Let them know they’ll need to show up prepared, with a thorough knowledge of the text you’re exploring. Explain that every student will be expected to participate, and all ideas are valid as long as they’re supported by the text. Share your list of the top four or five questions you’d like students to consider while they prepare.

Let students know that while you’ll be there to begin and guide the discussion, once things get started, it will really be all about them. That means they’ll need to be thoroughly prepared with a good understanding of the text. However, it’s also OK for them to bring their own questions to the seminar, especially about something they didn’t understand. Their fellow students can help them find answers to those questions too.

Encourage students to read the text through once to get acquainted with it. Then, they should review the questions you prepared, and reread the text with them in mind. They should make lots of notes, marking their text to make it easier to find what they’re looking for during the seminar.

They don’t need to write their answers to the questions out completely; instead, they should jot notes and highlight portions of the text they feel are relevant to these questions. That way, they’ll be more prepared to participate. The more familiar they are with the text overall, the better the seminar will be.

Socratic seminars usually take place with students sitting around a table or with their desks pulled into a circle. Participants should feel like an equal part of the discussion, with no one at the head or more important than anyone else.

Because most classes are larger than the ideal Socratic seminar size (10-15 students), many teachers use a “fishbowl” setup instead. One group of students sits in the inner circle, participating in the initial discussion. The rest sit in the outer circle, observing and taking notes to share during the larger class debrief. Learn more about fishbowl discussions here.

Before you begin, remind students that everyone is invited (and expected) to participate. Consider having each student give a response to the opening question before allowing others to chime in again or move on to another topic.

Your opening question sets the tone for the discussion. Choose a fairly broad question about topics like theme, characterization, ethics, or personal connections to get things going. However, avoid questions that are too generic, like “What did you think about this text?” or “How did this text make you feel?” Instead, try something like “What central themes did you identify as you read this text?” or “What connections did you draw between the historical events in the text and our current culture and society?”

As students begin to respond, step back and listen. Your job as a teacher is to keep things on track and ensure everyone’s voices get a chance to be heard. But try to resist stepping in at the first sign of trouble. Allow students a minute or two to resolve differences of opinion on their own. Give less confident students a bit of time to grow more comfortable before inviting them to speak.

If the discussion does seem to go off the rails, step in and gently redirect it. You can do this by prompting them to return to the questions you asked them to prepare for. You might also need to remind them to use textual evidence to back up their points, or encourage everyone to participate.

At first, students will likely look to you for direction. Resist the urge to lead the discussion, and instead ask more open-ended questions for them to consider. Whenever possible, simply listen and observe, taking notes of your own to share at the end.

As your time draws to a close, ask students to reflect on their discussion and try to capture their key insights. If you’re using the fishbowl method, now’s the time to let the outer circle speak up and share what they noticed. Ask participants to think about what they agreed and disagreed about or any issues they left unresolved. Encourage them to consider how their own opinions evolved throughout the discussion, and what they found particularly effective (or ineffective) about the process.

Finally, share your own observations and reflections about the seminar. Help students see what they’ve learned collectively, identifying key insights and connections to learning objectives. Share your own thoughts on any unresolved questions or issues.

If time allows, open the floor one last time for any final thoughts. Then, thank every participant sincerely for sharing their thoughts and evidence-based opinions, and for listening actively and respectively to what others had to say.

These questions are open-ended and thought-provoking. They require students to understand the text thoroughly, encouraging critical thinking and deeper analysis. Looking for more? Check out our list of 100+ critical thinking questions here.

Don’t forget to grab your free printable copy of this list of questions!

Just fill out the form on this page to get your free printable list of Socratic seminar questions to try with your class.